From its inception in 1923, the idea for creating a national park of the Smoky Mountains area was fraught with seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Financial, cultural and political issues were overcome to create what is today the most visited national park in our American Park system. The following is a brief synopsis of how the Great Smoky Mountains National Park came about and who the dedicated and visionary individuals were that stuck with the effort for 17 years until the Park’s dedication in 1940.

The idea began simply enough….

The original idea for a Smokies national park came from a wealthy and influential family in Knoxville, Tennessee. Mr. and Mrs. Willis P. Davis (pictured), after returning from a visit to western national parks, began asking, “why can’t we have a national park in the Smokies?” From this beginning, other influential citizens of Knoxville began to echo the sentiment. Politicians, businessmen, naturalists, and others began to join the movement for their own personal reasons.

Sometimes a movement gains momentum due to its own sheer power—it’s simply a good idea. Other movements succeed because of strong-willed, influential, wealthy individuals with a vision. The movement to create a national park in the Smoky Mountains was fortunate to have both elements. But this was not to say that things went quickly or easily—quite the contrary. Obstacles to Creating the Great Smoky Mountains National Park There existed natural foes to developing a national park. These foes consisted of financial interests to businessmen, political foes that had their own ulterior motives, and cultural foes that wanted the Smokies to remain as they were. Some businessmen were primarily interested in developing a road between Tennessee and North Carolina to make their business easier.

railway used to move the timber from steep mountain slopes to mills in the foothills

To them the Smokies were the place where they got away to hunt and fish. Other business owners were more interested in developing the Smokies as a national forest rather than a national park—the distinction being that national-forest status would still allow the area’s resources to be exploited; whereas national-park status would protect, for all time, the area just as it was (no timber cutting, hunting, or fishing). Chief among the business interests were the timber and pulp companies, which owned most of the wilderness areas and virgin forests. In addition, cultural interests included the families who already lived in the mountains, both descendants of the original settlers in the area and people who had purchased land for vacations or retreats.

Then, of course, there was the obstacle of acquiring the funds necessary to purchase all the land required to create the Park. Promises and contributions actually made up a small portion of the total funds required. Both the Tennessee and North Carolina legislatures, Congress, and the Rockefeller family would all come to the rescue.

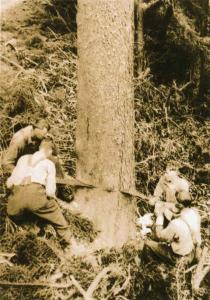

sawyers fell a tree using crosscut saws

Time and Money As mentioned previously, the original idea for a Smokies national park came in 1923. Actual fund-raising began in 1925. A bill to authorize and protect the area as a park was passed in 1926, but came with strict stipulations that a minimum of 300,000 acres be acquired and minimum commitments in funds be obtained. North Carolina supporters, who had held out for a national park strictly in North Carolina, finally came around for a shared border to a park and their legislature appropriated $2 million in 1927—but only if Tennessee matched it. Not to be outdone, Tennessee’s legislature appropriated $2 million the same year.

When it became clear that the funds appropriated and subscribed to that point was not nearly enough, Arno Cammerer of the National Park Service and Colonel David C. Chapman of Knoxville, convinced John D. Rockefeller Jr. to make a gift to ensure the success of the effort. The philanthropic Rockefeller family was kn

John D. Rockerfeller Jr

own to be sympathetic to national park causes (having contributed to the success of others) made a gift of $5 million to the effort, but only on the stipulation that it would be matching funds. To get the full $5 million, the states and park commission would have to come up with $5 million of their own.

With funds committed, 1929 was spent trying to get landowners to sell. This was a daunting task, because even though timber companies were the largest landowners, there were many other owners with very small tracts to obtain—over 6,000 in all. Many were descendants of original settlers, some simply loved their homes and didn’t want to move under any circumstances, and a few were big business interests such as the Little River Lumber Company and the Champion Fiber Company (the single largest owner) who held out for as much as they could. So in 1930, condemnation suits began. States had the right to “condemn” property for higher use. It wasn’t until 1931 that the Champion suit was settled. The Little River Lumber Company would settle too, but continued cutting timber for 7 more years. In June 1931 the Park’s first superintendent (Major J. Ross Eakin) and rangers reported for duty. The purchase of smaller tracts of land continued through 1932 (and would not be completed until 1939). In 1935, Franklin D. Roosevelt allotted more than $1.5 more based on new estimates of funds required to purchase lands. In 1936, the minimum number of acres was acquired to officially qualify for park development. Finally, 17 years after the initial idea, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was dedicated at Newfound Gap, which sits on the borders of Tennessee and North Carolina. Half on each state’s boundary, a plaque memorializing the Rockefeller Foundation gift was placed—a memorial to the single most important financial accomplishment in developing the Park.

Colonel David C. Chapman

Other memorials were created for those tireless and dedicated individuals who gave freely of their time and efforts to create the Park. Some of the highest peaks in the Park are named for these individuals. For the pioneers of the idea, Mt. Davis and Davis Ridge were named for Mr. and Mrs. Willis P. Davis. For Colonel David C. Chapman (photo, right), who accepted the idea from the Davis’ and helped get financial support from the Rockefellers, we now have Mt. Chapman. Mt. Kephart is named for Horace Kephart, who quit as a librarian and lived for years among the Smoky Mountains people (and wrote about them in Our Southern Highlanders).

Mt. Cammerer was named for Arno B. Cammerer, a director of the National Park Service.

Maloney Point and the Morton and Webb Overlooks were also named for individuals who accomplished much in the success of making the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Cost and Value

All told, the acquisition of lands needed for the Park totaled over $12 million. By today’s standards, the market value is immeasurable. However, the value then or today can’t be compared to what has been created and preserved in the form of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The diversity plants (more than 1,500 species), wildlife, recreation opportunities (800 miles of hiking and horse trails), trout streams, the blend of beautiful valleys such as Cades Cove and high peaks such as Mt. LeConte. If you have seen the Smokies in Autumn’s splendor, or Spring’s renewal, or even the breathtaking mountain vistas of winter, you know there is no way we can place a monetary value on the Park’s lands. In hindsight, business interests have to be pleased. The area gets 10 million visitors annually and revenues are such that Tennessee doesn’t have an income tax, due in large part to the popularity of the Smokies area.

What’s in a Name: Great Smoky (Smokey, Smokie) Mountains National Park

How did the Great Smoky Mountains National Park get its name? The Smokies are named for the blue mist that always seems to hover around the peaks and valleys. The Cherokee called them shaconage, (shah-con-ah-jey) or “place of the blue smoke”.

As for the spelling, just as many folks call them “smokey” as do those who call them “smoky”. The dictionary says both are acceptable. Whether you say Smokies, Smokys, or Smokys doesn’t really matter. They all conjure up the same vision that millions of visitors each year take with them after visiting the Park. As for the “Great” in Great Smoky Mountains, you will have to visit the Smokies to fully understand that part of the name.

Park Visitation

1940 Dedication by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

The first full year the Park was open, more than one million people visited. Visitation has grown steadily (except for the war years of the forties) until nearly ten million visitors annually enjoy the benefits of the National Park. Not all is well, however. The numbers are so great that the environment is adversely affected. The Smokies are even smokier than ever before. Pollution is beginning have a permanent effect on the beautiful mountain views. Development around the Park has created unbelievable traffic jams at certain times of the tourist season, particularly on weekends. Officials are exploring ways to solve these problems. It won’t be easy, because one huge promise was made in the original charter was that there would never be an admission charge and that the Great Smoky Mountains National Park would always be protected for the enjoyment of all the people for generations to come.

So the Park is still being “made”. We must do our part to enjoy the Park, but also help protect it for our future generations. Observe the beneficial restrictions that are placed on the visitor, and we can all enjoy the Park for generations to come.

More Park Information

We have tried here to summarize 17 years of effort and detail about how the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was created. A lot of detail is missing and perhaps some deserving individuals have gone unmentioned. If you want to learn more about the Park, its early inhabitants, and individuals responsible for creating the Park, obtain copies of the following books:

Our Southern Highlanders, Horace Kephart, 1961, University of Tennessee Press

The Making of A National Park, Carlos C. Campbell, 1964, University of

Tennessee Press

Photographs courtesy of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Service